Big Screen Poetry

In Don't Play With Your Food, Do Play With Your Poetry (11 June 2017), I pondered how I could draw lessons learned from studying a play script into my poetry. In this week's creative writing class, the last one of this academic year, we looked at scripts for the big screen and, once again, it made me really think about how I write a poem or sequence of poems.

Pacing the Story

Screenwriting is a definite craft, a definite art. Over the years, I’ve read thousands upon thousands of screenplays, and I always look for certain things. First, how does it look on the page? Is there plenty of white space, or are the paragraphs dense, too thick, the dialogue too long? Or is the reverse true: Is the scene description too thin, the dialogue too sparse? And this is before I read one word; this is just what it "looks" like on the page. You’d be surprised how many decisions are made in Hollywood by the way a screenplay looks—you can tell whether it’s been written by a professional or by someone who’s still aspiring to be a professional.

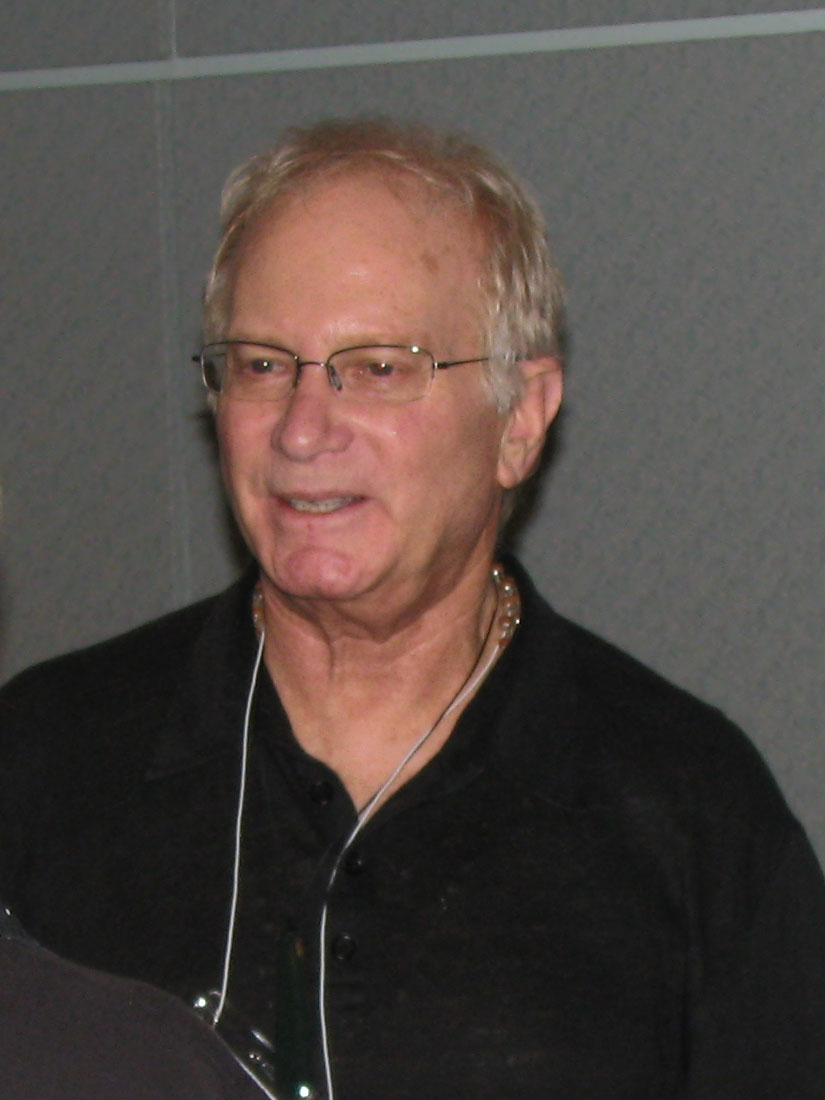

Those are the words of Syd Field (1935-2013), shown below in a photograph at the 2008 Screenwriting Expo, courtesy of Wikipedia. He was an American Screenwriting guru and his books have instructed and guided many burgeoning scriptwriters and film directors. All Syd Field quotes in this post come from his book, Screenplay, Revised Edition (2005).

In this digital age when we're drafting our work on computers, it can be easy to forget how it will look on paper under bookstore lights, not backlit and high contrast on screen, but that may be how an occasional poetry reader may first encounter it if they pick up your book, or an anthology that contains a few of your poems, and flicks through it, on the basis of which they will decide to read more or put it back on the shelf.

Obviously I can't see what a poem looks like on paper or screen anymore, but the same effect passes into how the poem sounds when I listen to it.

Beginning, Middle, End

Syd Field has a very clear structure for successful film scripts.

- Act I is a unit of dramatic (or comedic) action that goes from the beginning of the screenplay to the Plot Point at the end of Act I. There is a beginning and an end point. Therefore, it is a whole, complete unto itself, even though Act I is a part of the whole (the screenplay). As a complete unit of action, there is a beginning of the beginning, a middle of the beginning, and an end of the beginning. It is a self-contained unit, approximately twenty to twenty-five pages long, depending on the screenplay.

- Act II is also a whole, a complete, self-contained unit of dramatic (or comedic) action; it is the middle of your screenplay and contains the bulk of the action. It begins at the end of Plot Point I and continues through to the Plot Point at the end of Act II. So we have a beginning of the middle, a middle of the middle, and an end of the middle. It is approximately sixty pages long, and the Plot Point at the end of Act II occurs approximately between pages 80 and 90 and spins the action around into Act III. The dramatic context is Confrontation.

- Act III is the end, or Resolution, of your screenplay. Like Acts I and II, Act III is a whole, a self-contained unit of dramatic (or comedic) action. As such, there is a beginning of the end, a middle of the end, and an end of the end. It is approximately twenty to thirty pages long, and the dramatic context is Resolution . Resolution, remember, means "solution," and refers not to the specific scenes or shots that end your screenplay, but to what resolves the story line.

Novels have a beginning, middle and end. I've seen many short story competition summaries where the judge(s) have noted that the most successful entrants had written a story with beginning, middle and end. Poems too have a beginning, a middle and an end and strong poems incorporate that into their shape and content.

I have never heard a poetry workshop tutor talking about poems needing to have this kind of structure, and maybe that's because a poem is usually a very intense snapshot, condensing a film's worth of emotion into comparatively few lines. The art in poetry is putting a scene in the spotlight whilst leaving space for the edges and shadows of the surrounding world to slip in.

Order, Order

My gut feeling is that poets can benefit a lot from thinking about their poems in the structural form Syd Field details for movie scripts. Balancing the length of the component parts of a poem can help it flow and bring out the humour, the emotion, the heartbreak, the angst and the anger that the poet wants the reader to feel at exactly the right point in the poem. I've read several writing guides that extol starting short stories right in the middle of an action scene, not spending 6 pages setting the scene before anything particularly exciting happens. When a poem is being created it can be helpful to begin it with some scene setting from which the poem will develop, but if a poem of 40 lines has 8 lines of scene setting, then it's probably not grabbing the reader's attention as well as it could do.

The Poetry Tarot

And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

Which I am forbidden to see.

(from T. S. Eliot, The Wasteland)

Consulting the tarot deck should be part of every poet's education, but I think Syd Field's use of cards might be more helpful to me at this point. Syd suggests:

How do you build your storyline?

By using 3 × 5 cards.

Take a pack of 3 × 5 cards. Write the idea of each scene or sequence on a single card, and a few brief words of description (no more than five or six) to aid you while you’re writing. You need fourteen cards per thirty pages of screenplay. More than fourteen means you probably have too much material for Act I; less than fourteen means you may be too thin and need to add a few more scenes to fill out the Set-Up.

This ties in very neatly with some advice I received from Daljit Nagra on the Arvon course I attended at Lumb Bank in November 2016. When we looked at chapter 1, Silent Night, of my short story in verse, Plastic Life, he suggested I give each of the chapters a sub heading, such as:

Silent Night

In which our protagonist reflects on his wife leaving him at Christmas

I didn't feel that was what I wanted for every chapter of the story, but it would definitely help me get a firmer grasp on the movement and pace of the poem, which chapters are action chapters and which are reflection ones, and whether there's a doldrum of reflective chapters where the protagonist regrets shooting his metaphorical albatross. That's going to be my next focus of activity on Plastic Life over the summer break.

Turning the Tables

Films do get made about poetry, but tend to focus on the poets more than the poems. A Poet in New York, commissioned for the BBC, for example, dramatises Dylan Thomas's last few months in New York City. If I could see my photo scans I'd post photos of me outside Hotel Chelsea and drinking a pint outside the White Horse Tavern, the latter being the scene of Dylan's legendary last whisky binge.

Thomas expert George Tremlett did not understand why the BBC had chosen to commemorate the centenary the poet's birth by making a film about his death.

(Wikipedia)

... and to pinch one more quote from the Wikipedia page:

Ceri Radford, in The Daily Telegraph said: "[Tom Hollander] made a startlingly good Thomas, while the script came from one of the few writers who could hope to do the poet justice." and "This was tragedy in the Shakespearean sense: a great man undone by one fatal weakness. ... The production was lush, lyrical and very, very funny."

(The Daily Telegraph)

I think every poet deep down knows that fame only arrives at the point you're no longer around to properly toast it ;)

One exception to this made it to the small screen in 2010. The Song of Lunch, a dramatisation of Christopher Reid's poem of the same name, starring Alan Rickman and Emma Thompson. Rather curiously the production is unusual in featuring little spoken dialogue, the action instead being an enactment of incidents described in poetic monologue by the male character.

Cut

Joe Gillis: You're Norma Desmond. You used to be in silent pictures. You used to be big.

Norma Desmond: I *am* big. It's the *pictures* that got small.

William Holden as Joe Gillis and Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard

... Talking of lunch, my stomach is rumbling and I am in need of a cup of decaff too so, until next week, :)

#Screenplay #SydField #DaljitNagra #ShortStories #PlasticLife

Be First to Comment